Some of the vendor briefings we’ve participated in during the last six weeks have led to some pretty intense philosophical discussions. How is “virtual” different from “real?” How is “real” different from “realistic?” These questions are important to work through not as ethereal brainteasers but because 1) many people call this category we cover “virtual worlds,” 2) and many people tend to distinguish virtual worlds from “the real world,” and 3) virtual worlds and the physical world are converging. The way we see it:

- “Virtual” and “real” are not opposites. We think a better way to make the distinction is “virtual” vs. “physical.” Why? It’s all real. Meeting with one colleague in Second Life is no less real than going out for a coffee break with another colleague. (Well, perhaps this depends who your colleagues are, right?) Think of a financial analogy. Depending on what you do for work, chances are you get your paycheck electronically deposited into your bank account. You likely see numbers on a bank statement (possibly on your bank’s Web site) (“virtual money”) and you trust that when you put your plastic card into an ATM machine and enter the right numbers, cold hard cash (“real money”) will come out. Just because you aren’t paid in cash doesn’t make your income any less real.

- Virtual and physical worlds are converging. During the next 3-5 years, the realism of the Immersive Internet will increase and interface devices (the mechanisms we use to interact with virtual environments –- like mouse, keyboard, computer screen, and haptic devices) will become more natural and less intrusive to use. And virtual environments will be integrated with an increasingly large array of external data sources. Together, these developments will make virtual worlds and the physical world increasingly difficult to tell apart.

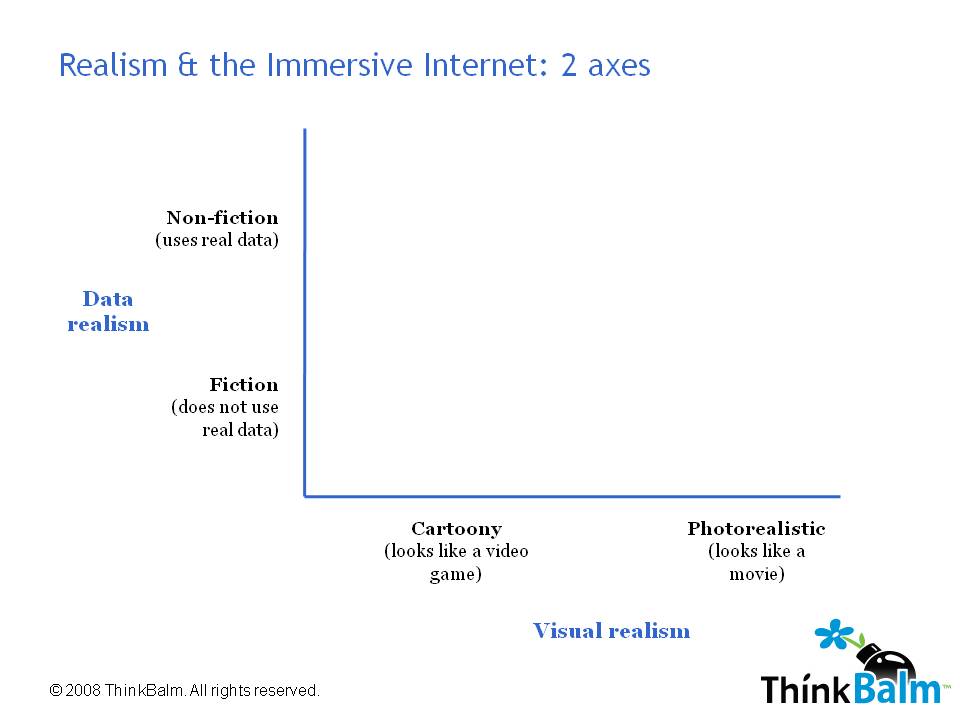

Two axes of Immersive Internet realism: visual and data

Realism is a very important Immersive Internet consideration. (See our June 30, 2008 article, “First life” versus “fake life” – When realism is important in the Immersive Internet.) It’s also confusing because there is more than just one kind of realism. We’ve boiled it down to the two most important axes:

- Visual realism: accurate representation without idealization. The dictionary definition of the word realism refers to what we think of as visual realism. According to Merriam-Webster online the definition of realism is “the theory or practice of fidelity in art and literature to nature or to real life and to accurate representation without idealization.” In our view this term applies not just to art and literature but to media (e.g., movies, TV, commercials) and the Immersive Internet. Note the word “representation” ― visual realism is a representation of reality, not reality itself. At one extreme, virtual environments can be very light on the visual realism; they can be cartoony, or video game-like. (Think Google Lively or ROCKETON.) Virtual environments that have a high degree of visual realism look as if they could be real; they can be photorealistic, or movie-like. Think Forterra OLIVE or Virtual Heroes HumanSim.

- Data realism: the virtual environment uses current, accurate information. Virtual environments that have a high degree of data realism use accurate and correct or real-time or near real-time data such as: weather, tracking (e.g., flight, fleet, cargo, package –- from, for example, radio frequency ID (RFID) or global positioning systems (GPSs)), system status (e.g., computers, engines, HVAC, security), or bills of materials (data about an object from a product lifecycle management (PLM) or computer-aided design (CAD)system). We think of the data realism continuum as being fiction on one end and non-fiction on the other. Some Immersive Internet applications will require a high level of data realism (non-fiction) ― for example, aerospace or automotive design simulations, in which engineers need to know not just how an object looks but exactly how it would work in the physical world. A training simulation to teach fast food restaurant employees to wash their hands for a full minute before returning to the food prep counter might require less data realism; non-fiction is adequate.

Based on these two axes, we draw on analogies from the book, movie, and video game worlds to describe four main categories of Immersive Internet applications: non-fiction video game-like, fiction video game-like, fiction interactive movie-like, and non-fiction interactive movie-like. For a discussion of these four categories see the July 21, 2008 ThinkBalm article, A realism model for Immersive Internet apps: Part II.